Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

Turkey is facing one of the worst humanitarian disasters of its history. On 6 February 2023, two massive earthquakes have hit the southern regions of the country in a span of 9 hours, leaving behind an unprecedented level of destruction. Ten cities (Maraş, Hatay, Adıyaman, Antep, Diyarbakır, Urfa, Elazığ, Malatya, Adana, and Batman) have been struck, with over forty thousand people killed at the time of writing. The government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is severely criticized for being slow to respond to the crisis and failing to deploy the search and rescue teams to the area in a speedy fashion, which may have significantly increased the death toll.

Meanwhile, those who were lucky to survive the initial shocks have been left homeless and more than 1.5 million people have been displaced, not knowing where to go. Almost two into the catastrophe, people continue to live under unsanitary conditions, with the lack of mobile toilets being a major issue in the region. Relatedly, reports from the earthquake-stricken areas warn of the possibility of a spread of infectious diseases, which would make life for the survivors even more unbearable.

The disaster has unleashed a growing anger against the Erdoğan regime and state institutions that the president himself came to represent, especially since he successfully pushed for a transition into the presidential system of government in 2017. Accusing the government of incompetence, the survivors complain about the state “leaving them alone” at a time when they most needed it. Although the Erdoğan government is trying to frame the earthquakes (and their aftermath) as far too big for any one government to handle, in actuality the destruction wrought by the disaster is directly linked to the policies the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan have pursued in their 20 year rule in general and in the last 10 years in particular. To be more specific, it can be argued that the political choices Erdoğan has consistently made over the last 10 years should be seen as the main culprit behind transforming the earthquakes of February 6 into one of the worst humanitarian catastrophes that modern Turkey has witnessed in its history.

Construction of a Calamity

Erdoğan’s over-dependence on construction both as the main propeller for the Turkish economy and as a function of creating a new elite loyal to himself was one of the primary reasons behind the scale of the recent tragedy. The construction industry has grown exponentially in AKP’s 20-year rule. Over the years, Erdoğan has aggressively pursued major infrastructure projects as well as polices for urban renewal in major cities, often in open defiance of scientific opinion. Many of these projects were given to a new circle of business elite, who in turn supported Erdoğan. One glaring example of how these policies came to a sad end was the Hatay Airport, which was constructed on the now drained Lake Amik in 2007 despite warnings from the experts to the contrary and which has been destroyed in the earthquake, preventing aid from reaching the city quickly. Moreover, many of the roads, state hospitals, and municipal buildings in the earthquake region, constructed during Erdoğan’s rule by his cronies, have collapsed, hindering the efforts of the rescue teams and volunteers during the crucial hours following the disaster.

Erdoğan also used the construction boom as a way to solidify his voter base. Despite the existence of strict building codes, which have been put into place after yet another massive earthquake that claimed more than 15,000 lives in 1999, the municipalities and ministries responsible for enforcing these laws have generally turned a blind eye to illegal constructions, underlining the corrupt symbiotic relationship between the politicians the construction industry.

Not only these illegal constructions were not demolished, but Erdoğan’s AKP has also granted a total of 9 legal amnesties for buildings constructed in violation of the building code since 2002 with the hopes of garnering votes from the electorate. The latest of these amnesty laws has been passed in 2018, right before the presidential elections, which the president has won with 52%. The President also used these amnesties as talking points during the local elections of 2019. Early reports indicate that up to 294,000 buildings in the region have benefited from the amnesty in 2018, many of which have collapsed in the latest earthquakes, killing thousands and injuring many others.

Hollowed Out State Institutions

Another factor exacerbating the magnitude of the crisis that continues to unfold since February 6 is Erdoğan’s efforts to over-centralize and gather all the power of the state unto himself, in effect creating a one-man rule. More specifically, this over-centralized style of government led to the hollowing out of the state institutions, which almost ceased to have an existence independent of President Erdoğan and lost their ability to function properly.

The mirror image of these efforts to create an over-centralized one-man rule was the persecution of civil society initiatives, such as the Union of Chambers, which has consistently critiqued the Erdoğan government’s construction policies and which the Erdoğan regime has perceived as a threat to its survival. The most glaring example of this aggressive stance against the civil society was the jailing of Mücella Yapıcı (architect), Can Atalay (lawyer), and Tayfun Kahraman (urban planner) on bogus charges related to their role in the Gezi Protests of 2013. Another example is AKUT (Search and Rescue Association), which came to prominence in the aftermath of the 1999 earthquake and was mostly hollowed out and recently taken under indirect government control due to AKUT’s former president Nasuh Mahruki’s anti-AKP views.

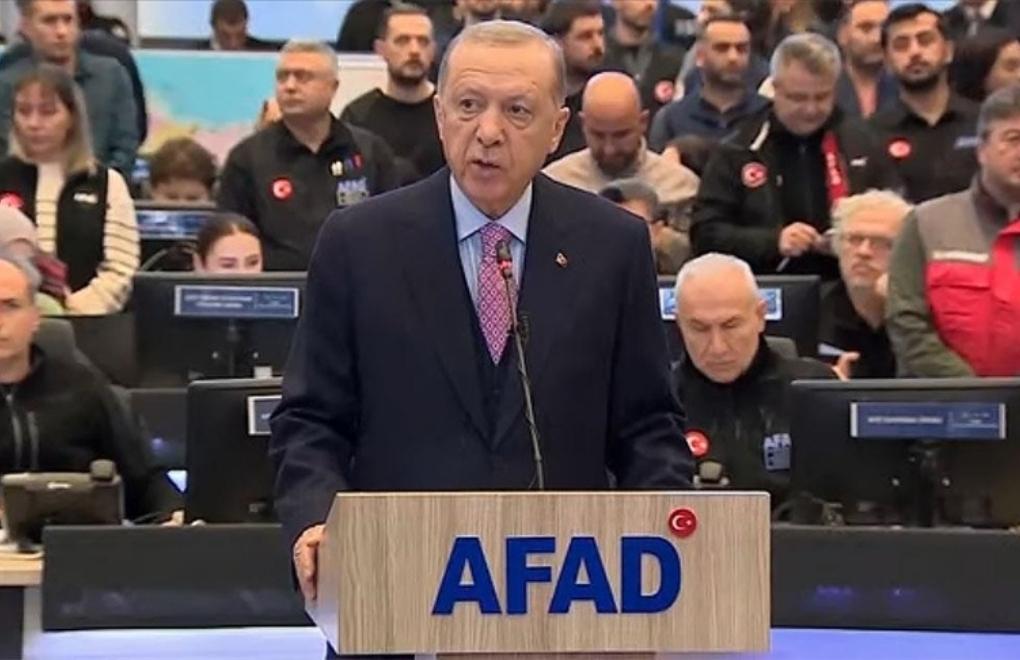

This overly centralized style of government, however, came crashing down on top of people in the region during the earthquakes of February 6. The state apparatus broke down almost completely in the first 48 hours of the disaster. Ministry of Interior’s Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency (AFAD), whose main goal is “to minimize disaster-related damages, plan and coordinate post-disaster response, and promote cooperation among various government agencies” utterly failed to do its job. The deployment of search and rescue teams, both from within Turkey and abroad, as well as volunteers and equipment, was delayed mainly because there were no clear directives coming “from above.” Turkish military personnel and Turkish miners, who had played a significant role in the rescue operations in the aftermath of the 1999 earthquake, were sent to the area late and few in number. Distribution of food and medical supplies as well as tents suffered from a lack of coordination, with people ending up lacking basic necessities well into the second week of the disaster. In short, the earthquakes proved the image of government promoted by Erdoğan (strong and efficient with a propensity to take quick and accurate decisions) to be a mirage rather than a reality.

Political Implications

In a more general sense, the disaster that struck the country on February 6 laid bare the stark discrepancy between the discourse and actual capabilities of “state” (devlet) as a concept. Being aware of the dangers of falling into the trap of essentialism, it may be argued that “the State” is almost reified in Turkey as an omnipresent and omnipotent being. Erdoğan leaned heavily on this rhetoric and came to represent himself as the personification of “the State,” especially after the transition into a presidential system of government.

This all-powerful entity, however, was nowhere to be seen in the crucial hours following the earthquakes on February 6. Instead, the state tried to make its presence felt by other means. For instance, two days after the earthquake, the government shut off Twitter, which was used by people in the region to reach their loved ones under the rubble and organize aid efforts in the area, for almost a day to stem off criticism that shed light on the government’s inadequacies. Moreover, the police arrested a number of individuals for disseminating “misinformation” on social media. These moves, however, backfired completely and added fuel to the fire, making people even angrier against the government. It is telling that even in AKP strongholds such as Maraş and Adıyaman, anger against the Erdoğan regime is palpable, as can be seen in the video clips that circulate on social media.

Seen in this light, it may not be too far-fetched to argue that the earthquake will have severe political consequences for Erdoğan and his AKP. Similar to what had happened in the aftermath of the 1999 earthquake, which paved the way for the rise of the AKP as a major force in the Turkish political scene, the disaster of February 6 may be a turning point for Turkish politics in the near future. It should also be emphasized that while the Erdoğan government was floundering to come up with a coherent response to the crisis, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, leader of the main opposition party, immediately went to the region and pointed to Erdoğan as the main culprit of the disaster, which was generally perceived as a positive move on the opposition’s part. If the opposition bloc succeeds in channeling the anger of the electorate and convince them of the urgent the need to construct a more functional system of government, they may put an end to Erdoğan’s rule in the next general election.