Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

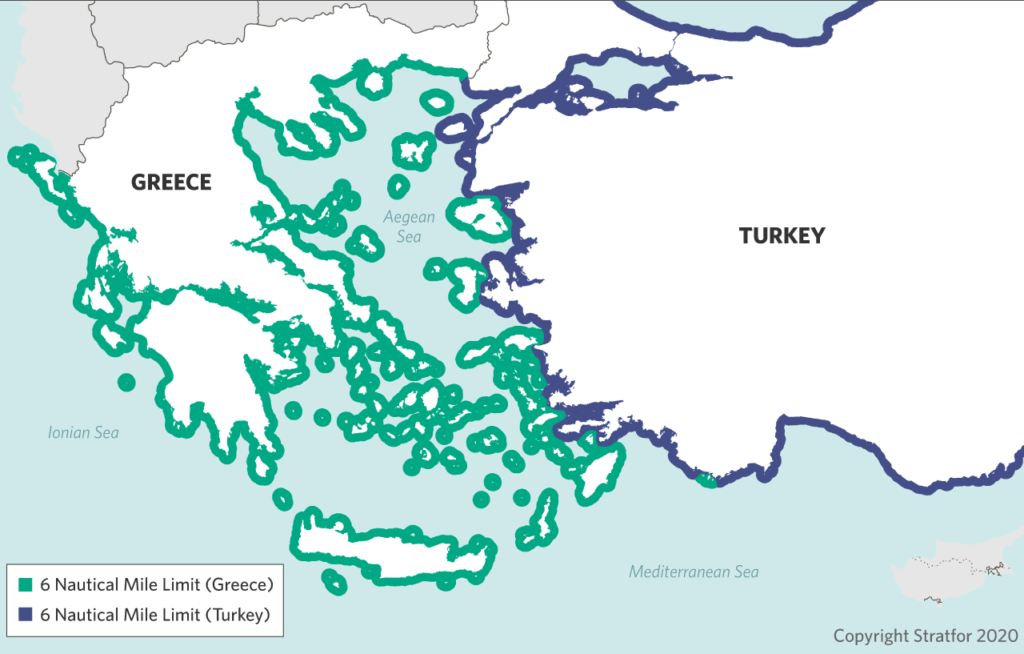

Tensions between Turkey and Greece have been escalating recently over the militarization of Greece’s eastern Aegean islands and disputed air space between Turkey’s mainland Anatolian shores and the islands. Both sides accuse each other of violating the international law: Greece argues that Turkey does not respect its 10 Nautical Miles(NM) airspace over the islands while Turkey claims that any space over 6NM is an international zone both in the sea and in air as there is no definite agreement on further claims between the neighbouring countries. Moreover, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu raised the concern last week that if the islands are kept militarised, their ownership by Greece would be challenged based on the Lausanne and Paris Agreements, signed in 1923 and 1947 respectively.

Some of the islands, which the Ottoman Empire lost to Greece and Italy during the Balkan Wars (1912-1913), are just 2-3 KM away from Turkey’s mainland Anatolian shores. In 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne between Turkey and Greece returned Gökçeada (Imbros) and Bozcaada (Tenedos) to Turkey and confirmed Greece’s sovereignty over the other Aegean islands. The treaty drew 3 NM territorial waters for the sides. However, some Turkish officials also argue that the treaty does not specify sovereignty over small islets which are out of 3 NM. In 1936, Greece unilaterally increased its territorial waters from 3 NM to 6 NM, and Turkey followed its neighbour in 1964 although the sides never agreed on 6NM on paper. However, Greece claims that it keeps the right to expand its territorial waters up to 12 NM, while such an amendment is regarded as casus belli according to an edict passed in Turkish National Assembly in 8 June 1995, a week after Greek Parliament allowed the government to expand Greece’s territorial waters up to 12 NM in the Aegean Sea. In fact, both countries were on the brink of war in December 1996 for two islets, Kardak/Imia, just 3 NM away from the Turkish shores. Both sides sent commandos to claim the islets even though at the end the commandos were called back mutually but the issue was not solved and was just postponed. Therefore, it is still an inevitable dispute today for sea and air zones between the two countries.

Furthermore, both Greek and Turkish sources argue that Erdoğan escalates the tensions because of the critical elections coming up in June 2023. By doing so, it is considered that he aims to evoke nationalist votes to support him. For this reason, Erdoğan uses a very simple language that could be colloquially understood rather than a language of diplomacy. He even posted a tweet in Greek addressing the people of Greece and referred to the Turkish War of Indepence (1922) which led to a great catastrophe for Greece while resulting in victory for the Turkish side. Erdoğan has addressed the Turkish voters and the Greek people rather than his official counterparts because he blames the Greek PM Kyriakos Mitsotakis of not being a ‘man of his word’. This is mainly because of the fact that although the two had agreed on not getting third parties involved in the Turkish-Greek disputes during their meeting in İstanbul a couple of months ago, the Greek PM complained about Turkey in the US Congress. Moreover, Erdoğan criticised Mitsotakis for lobbying against Turkey’s intention to modernise its F-16’s and to return to the F-35 project, from which Turkey was kicked out because it had purchased S-400 missile systems from Russia. Erdoğan said that he would never meet with Mitsotakis again. In a similar way to Erdogan, the Greek PM also signalled last week for an early election by stating that a later election could cause more polarisation and tension with regards to Turkey. It can be interpreted as a sign that Mitsotakis believes that higher tensions with Turkey in the upcoming months could weaken his hand for the scheduled election in spring 2023; therefore, he could prefer having a snap election while the wind still favours him against his rivals. In light of this analysis, it can be argued that even though the tensions between Greece and Turkey strengthen political actors’ populism for elections it also damages the opportunities for cooperation between the two countries.

Other discussion channels, such as the Greek-Turkish committee for preventing escalation, also seem frozen for some time although officials from both sides claim that the dialogue channels are open. For example, Turkey’s defence minister Hulusi Akar mentioned at the Political Committee of the NATO Parliamentary Assembly (NATO PA) meeting (14-17 June) in Istanbul that the fourth meeting was supposed to be held in Turkey but the Greek side did not show any signs to attend. Meanwhile the Greek officials announced that the door for dialogue is always open and that Erdoğan’s attitude was not helping. Akar, who was the Chief of Turkish General Staff prior to joining the cabinet in July 2018, suggested that both countries’ military staff should offer solutions to politicians to be approved or disapproved without involvement from third parties such as the US or the EU.

Due to the collapse of the dialogue, rumours occupy the ground such as that Erdoğan has an invasion plan for Greece in his mind. Some Greek media sources base this claim on Erdoğan’s asking for a parliamentary permission to send troops to ‘countries’ rather than naming a country which could be Libya or Syria where Turkish troops are currently present. Former general staff and vice minister of Defence Alkiviadis Stefani also argues that Erdoğan is likely to be escalating the tension for the elections and that the issue of refugees could trigger the first fire between the sides. In fact, on 20 June, Monday Erdoğan criticised Greece for pushing back and robbing migrants while the Greek officials rejected his claims. Turkish officials, in a parallel way with Erdoğan, strongly condemn the Greek government for causing death-resulted push back cases, which are also reported by independent sources such as Border Violence and Der Spiegel. In fact, after the reports were published, Fabrice Leggeri, the head of Frontex, the EU border agency, had to resign because it was revealed that he knew about the illegal push-backs. The argument that Erdoğan is bluffing for the elections may be true but the airspace and border disputes between the two countries have been present decades before Erdoğan’s tenure. After the foundation of the modern Republic of Turkey in 1923, Ankara, especially the General Staff of the Turkish Armed Forces, tried to secure its western shores even when the Dodecanese islands were under Italian rule until 1947. The sides signed an agreement on 11 November 1976 in Bern in order not to undertake any delimitation without a settled agreement, but in the late 1980s both countries were about to fight over some gas fields in the north eastern Aegean prior to the Kardak/Imia crisis mentioned earlier.

Maximalist policies and lack of empathy towards the other keep the discussions away from any concrete solution. For example, Greece refers to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of which Turkey is not a signatory to justify its 12 NM continental shelf, which would lock Turkey to its mainland shores and make Turkey dependent on Greece’s permission to cruise. While Greece wants to use its right given by the international law, Turkey holds forth that the Aegean Sea is a special, unique case where 12 NM right cannot be applied easily. Under any legal consideration, the islands in the eastern Aegean Sea are so close to Turkey’s mainland, and maximalist claims over territorial sea, exclusive economic zone (EEZ), and airspace makes clashes unavoidable. Also, Turkey supports the “Blue Homeland” doctrine rejecting EEZ for the Aegean islands, and claims pretty much half of the Aegean Sea based on Greek and Turkish mainland shores. In the end, more areas are disputed due to mutual maximalist claims which make negotiations more essential.

On the one hand, Athens seems to be looking for external support for its position and arguments rather than negotiating the issues with Turkey. Greek officials, for instance, often mention the European Union as a side when referring to their disputes with Turkey such as the Agean maritime and air zones, and even Cyprus as EU matters. Moreover, Greece seeks support from the US, and as a result it has recently provided some military bases for the US army in the country. However, the Greek opposition criticises the government for allowing more US troops and military bases to be stationed in the country. On the other hand, Turkey does not even trust its NATO allies such as the US, whose bases, especially the one in Alexandroupoli is 40 km away from the Turkish border, are against Turkey. Lately, former PM and the current leader of opposition in Greece, Alexis Tsipras, mentioned that Greece would remain alone when it comes to defending the country despite all the promises and diplomatic support from the EU and the US.

Tsipras probably thinks that no country would join a war with Greece against Turkey, who is a significant NATO member with its important geopolitical location. Turkey, however, considers that the European powers and the US do not treat Turkey as their equals, so they would not alter their stance whether Turkey is right or wrong. For example, Turkey was excluded from the F-35 project for having Russian-made S-400, Turkey criticised its allies for not being fair while Greece, as a NATO member, possesses S-300.

In conclusion, Turkey and Greece need more effort to solve their problems but the potential political gains or concerns for political loss prevent sides from effective negotiations. The confrontation raises populist tendencies and detracts the sides from solution options. There is also an imbalance between Turkey and Greece. The former, with its military power, presents a stronger hand while the latter uses its political and economic alliances together with its stronger diaspora, which can be influential especially in the US. However, triggering a war would be something neither side would like to handle even for winning an election. The effects would be catastrophic not only for the warring sides, but also for the world in addition to the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War. Since for decades the same problems are still valid, it can be questioned that the sides do not have enough motivation to solve the issues despite their open announcements for it.